How to Engage Learners: Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction

After taking up a post as a neuroscience tutor, a family member kindly offered to run me through their instructor’s training course. A key component of the course was getting familiar with Gagne’s nine events of instruction. These events give you a framework for lesson delivery that is grounded in neuropsychological theory.

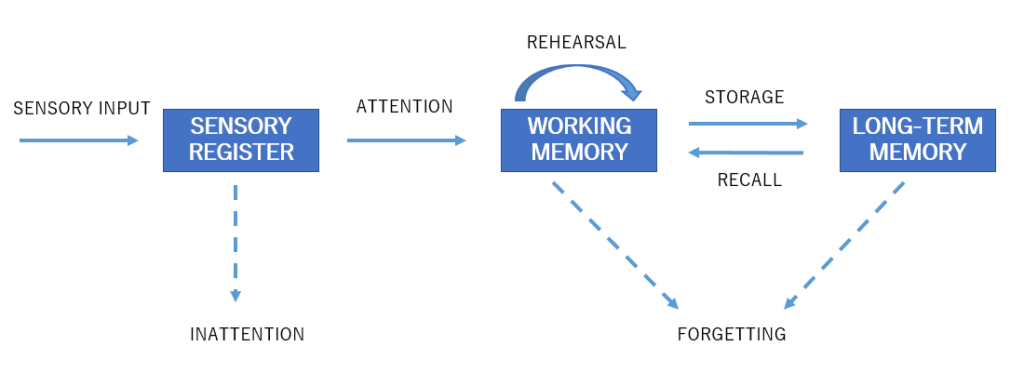

Gagne’s nine events of instruction were introduced in his textbook Principles of Instructional Design, published all the way back in 1974. Gagne developed his nine events from the information processing model of cognition: a model that is widely accepted by the neuropsychological research community. The first seven of these events should ideally occur within a single lesson to maximise the student’s learning. The final two concern long term retention of the material.

Tease their Attention

The first event is gaining the learner’s attention. You can see from the diagram of Atkinson and Shiffrin’s information processing in memory – no attention means that information never even makes it to working (short-term) memory! You have probably experienced this at some point in a class: where you suddenly “tune back in” and realise you have no idea what had been said in the last 10 minutes. The best way to gain attention is to use uncertainty or surprise. In my undergrad a lecturer once blasted Bowie’s Jean Genie at the start of a lesson – that certainly got my attention.

Note that gaining attention is not limited to the very beginning of the lesson. Students may begin to lose focus part way through, so it is good to use such techniques throughout the class.

Explain the Purpose of the Lesson

Next you want to inform the learner of the lesson’s objectives. This is important to engage your learner’s executive control processes. These processes are what allow the individual to pick a strategy for learning so that they can meet the objective. The course I attended had an entire lesson on this topic. It suggested giving learners three key pieces of information at the start of the lesson to allow them to pick a learning strategy: the lesson aims, learning objectives, and a session map:

- The aim of a lesson is a broad statement of its intent. It gives students an idea of what to expect from the class.

- A learning objective, or outcome, is an achievable and measurable statement of what the learner should know or be able to do as a result of the teaching. Learning outcomes for classes are often required by bodies that credit qualifications.

- The session map is just an outline of what will occur in the lesson. For example, a presentation followed by a group discussion session.

This second event in Gagne’s nine learning events is one that has been often overlooked in my own experience as a student but I think it is critical. It benefits everybody, but it is particularly important for making your teaching accessible. Individuals who struggle with focus; lack of structure; or prioritisation of tasks, like some neurodiverse individuals, will greatly benefit from clear direction on what to take away from a lesson.

Ask Them What They Already Know

The next event is simple: just ask the students what they already know about the subject you are going to teach. I have found this event extremely helpful in my work. I teach students who are located in the US, so due to the differences in school systems I don’t have a good understanding of what they will have covered in their biology class at a certain age. By asking them what they know, I ensure that my lesson is pitched at the correct level for them. It also gives me an opportunity to correct any misconceptions that the student might hold (and with neuroscience, there are plenty!).

Additionally, by asking a student what they already know, you are making them recall information from long-term memory that is relevant to what they are about to be taught. Now that this information is in working memory, it is easier for the student to understand the more advanced concepts that you will teach, which are highly likely to be built upon this previous understanding. The new information they learn will be assimilated with what they already know, giving them both a broader and deeper knowledge and understanding of the subject.

Create a Learning Experience

In event four, you must actually deliver the information you want to teach. How you present this material is important. All of the material included should address the learning objectives, anything superfluous should be cut. The lesson should also be structured in a meaningful way and ordered logically, as not to lose or confuse the student.

Gagne also emphasises that variety is key. This was well demonstrated in the content of the course I attended. Lessons included verbal delivery, slides, relevant video content, engaging me with questions, assigning written exercises, short article snippets to read, and (if there were other people) group discussion. A variety of material keeps students engaged, preventing information from being lost through inattention. It also gives them multiple opportunities to pick up on information if one attempt was unsuccessful.

Help Them to Remember

To make any use out of what you are teaching them, a student is going to need to be able to recall the information from long term memory at some point in the future. Therefore, it is important that you help them to remember what they have been taught. Recapping at regular intervals and repetition of key points helps students transfer information from working to long term memory, as will the aforementioned variety in content.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the memory is easy to recall. I am sure you will have experienced many times in your life when you have felt like a fact is “on the tip of your tongue”, but you just can’t remember it. And then, a little later on, some trigger suddenly causes you to recall it. Good teaching will provide students with cues that they can use to retrieve what they have learned from their long term memory. These could be acronyms, rhymes, or absurdist mental imagery. One key technique recommended by Gagne is to quiz your students. You’re not interested in the questions they get right – you are interested in the one they get wrong. Try your best to get your student to the answer without actually revealing what that answer is. I have found that my students have responded very well to this, and it also acts as a sneaky review of other material.

Examine Their Performance

Quizzing your students is one way to examine their performance, the sixth of Gagne’s events. Exactly how you examine performance will depend on your subject. It will show you and the student that they have successfully committed the information into memory. It is also an opportunity for repetition of material. Repetition strengthens the individual’s ability to recall the information.

Respond to Their Performance

The seventh event is to respond to that performance: communicating to the student their strengths and weaknesses, and how they can be addressed. Anyone who has had only past papers with no answers as revision material knows the frustration that comes with not having any feedback on how well you are doing. This is a key part of learning: positively reinforcing the correct information, and correcting misconceptions before they become engrained in someone’s memory.

Summarise the Impact on the Student

Whereas all of the previous seven events concerned a single lesson, we will now consider what happens after. The eighth event is evaluation of the impact of the teaching on the student. This is typically done through some kind of assessment like an exam. It motivates the student to continually review the material, further reinforcing their learning. Referring again to the diagram of Atkinson and Shiffrin’s information processing in memory, forgetting can still occur from long term memory. This means that very good performance of a student in a lesson does not necessarily equate to them having mastered the material. Thus, follow up should always be performed when possible.

Ensure Lasting Retention

The final and ninth event is creating lasting retention of the information. Again, it is possible for unused information to be lost from memory at any point. If the information necessary was required for a job, for example, regular review of staff’s understanding will be required even after the assessment associated with the course. A great way to encourage lasting retention of information is to make students apply the lessons learned to new problems and situations. Thankfully, this is usually a natural consequence of knowledge required for jobs, and results in individuals becoming extremely well versed in the subject.

Despite never having heard of Gange before taking the instructor’s course, he and his nine events of instruction are now becoming embedded in my own long term memory as I use his techniques to tutoring neuroscience to Brain Bee competitors.